A few months after the final mining ban in China, the new global mining landscape is crystallising. It is more decentralised and sustainable and stretches from Siberia and Central Asia to North and South America. Europe hardly plays a role – and if some government representatives have their way, even that is too much.

It’s nice to be a Bitcoin miner, nice and above all lucrative. But miners’ lives are not easy at the moment. First, miners set up shop in China, where, close to dams, coal-fired power plants and chip factories, they built huge mining farms. As recently as 2019, China accounted for about 75 per cent of the global hashrate, and all other countries were mining dwarfs compared to the People’s Republic.

But then the government banned mining, first partially, then completely, and the miners had to leave the country. You can think of it as an exodus: The miners dismantled their hardware, packed it in boxes, and fled. Where to didn’t matter at first. The main thing was that mining was not forbidden and electricity was cheap.

Several countries were happy to take in the miners. Kazakhstan, Russia and the USA were always under discussion, but the actual distribution of the miners remained a matter of speculation. Analysts like the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance do show in statistics where approximately the hashrate originates, but such data is usually not very reliable.

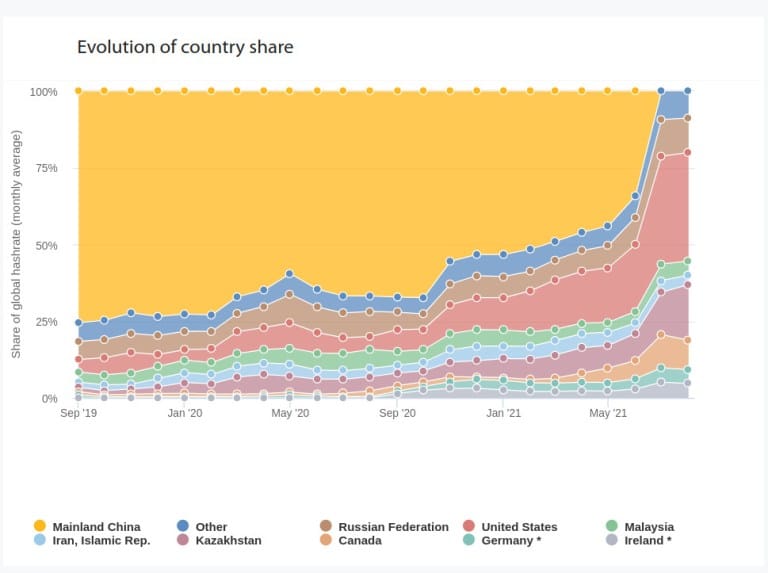

Distribution of global hashrate by country as estimated by the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

Now the Financial Times (FT) has researched where Chinese miners have shipped their mining hardware to. To do this, the magazine probably interviewed the major mining operators. At least that’s my guess – because the article itself is behind a subscription paywall, which is why I can only quote it from other sources.

Where the miners are fleeing to

The mining ban, says the FT, “has sparked a global race to relocate millions of clunky, power-hungry machines that solve complex puzzles and earn bitcoins.” Fourteen of the world’s biggest mining companies had “exported more than two million machines from China in the months after the ban.” Another 700,000 machines that are either broken or obsolete are said to be lying in warehouses. They are, to put it harshly, e-waste.

Let’s pause for a moment at this point to digest the numbers. Two million miners. That’s two million devices like the Antminer S19, the AvalonMiner 1246 or the WhatsMiner M31S. They all have a power consumption of about 3000 watts, which means that two million miners consume about 6 gigawatts of electricity. For comparison, Germany has about 214 gigawatts installed, Belgium about 21.5, so it’s not trivial to generate these mining plants with energies. We will come back to that in a moment.

But first, let’s talk about who is the winner in the global competition for miners. According to the FT, the lion’s share of the equipment went to four countries: the USA, Canada, Kazakhstan and Russia. However, it is apparently only known where a good 430,000 devices ended up. Of these, 200,000 are now in Russia, almost 88,000 in Kazakhstan, 87,000 in the USA, 35,000 in Canada, 15,500 in Paraguay and another 7,000 in Venezuela. What happened to the rest is apparently unknown. Possibly it is a random sample and one would have to quintuple the concrete numbers.

But even so, the new mining hotspots reveal themselves with crystal clarity: in Siberia and Central Asia (Russia and Kazakhstan), North America (USA and Canada) and South America (Paraguay and Venezuela). This was tending to be foreseeable.

“A natural location for miners. “

As Bitcoin Magazine explained back in early November, Russia was benefiting from the exodus of Chinese miners. While China’s share of the global hashrate had fallen from 45 to 0 percent, Russia’s had risen from 7 to 11 percent and had the best prospects of rising further. Because Russia, the magazine said, was “a natural location for mining”.

No place is better suited “than the Irkutsk region of Siberia, where most Russian mining takes place.” The region has an abundance of hydroelectricity, it says, with only about 20 per cent of the electricity produced being consumed. In addition, the region’s cold cools the miners, making it cheaper, easier and safer to run a farm.

But miners are special. Wherever they find good conditions, they become bottomless consumers of electricity. In 2021, electricity consumption in Irkutsk rose rapidly by 159 per cent because of an “avalanche of underground miners”, according to Governor Igor Kobzev. The situation was getting out of control, straining the grids and threatening to lead to accidents and outages, he said. The governor called for special electricity tariffs to be imposed on miners.

In addition, miners are suffering from a problem that seems strange for Russia. A spokesman for BitRiver, a very active mining operator in Irkutsk, said that the problem in mining at the moment is not equipment, but space. Presumably, he means developed space for mining farms, which need not only strong power lines but also a good internet connection.

Cheap electricity alone is not enough to become a mining hotspot. Iran has already experienced this, where miners brought the power grid to the brink of collapse despite abundant surplus resources.

Power shortage in Kazakhstan

Similar reports are coming out of Kazakhstan. The country initially welcomed the miners by investing hundreds of millions of dollars to support them and provide a new source of income from its abundance of fossil fuels, mainly coal-fired power. A government report as recently as October predicted that mining could generate about $1.5 billion in tax revenue.

Winter is approaching in Kazakhstan, and Kazakhstan is facing a power shortage. The government is preparing for action. South Kazakhstan faces the risk of strict mining power restrictions.

Electricity shortages in Kazakhstan are the norm in winter, bitcoin mining in Kazakhstan– UNISTAR (@unistarmining) September 24, 2021

Now, however, it turns out that Kazakhstan’s power grid was not ready for the flood of miners. Already at the end of October, the country had to import electricity from Russia because of the threat of a winter power shortage. The government rushed to blame the miners. According to Energy Minister Murat Zhurebekov, they had increased electricity consumption by eight percent in a short time compared to the previous year.

The main problem is illegal and underground miners whose consumption is difficult to control. These farms, which allegedly account for two-thirds of Kazakhstan’s mining, do not pay taxes, of course, which Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev acknowledged by saying, “we are number two in the world for cryptocurrency mining, but we see practically no financial return on it.”

While the first miners are already leaving the country as power outages no longer allow for reliable operations, the government remains committed to positioning itself as a mining site. Tokayev announced that nuclear power plants would be built to meet the country’s energy needs in the long term.

Good conditions in America

Miners currently seem to find the best site conditions in North and South America. The USA and Canada in particular offer a colourful mix of energies – from coal and nuclear power to hydro and solar energy – as well as a stable political situation and good infrastructure.

Accordingly, the USA has replaced China as the global capital of mining. Around a third of the global hashrate now comes from the United States. In April, it was still 17 per cent. This development fits in with the trend in the US of individual regions and cities competing for the crypto industry. There are clear differences between the states and between the states and the federal government. But overall, miners in the US enjoy a secure and long-term base, sufficient power, a strong infrastructure and a high level of legal certainty.

In addition, various advocacy groups in the US are pushing harder than anywhere else for miners to primarily use sustainable resources. The Bitcoin Mining Council, an industry association, continues to collect data on the electricity mix of North American miners, a good 65 per cent of which is renewable.

This shift in trend from China to North America should be good news for both the decentralisation of Bitcoin and the carbon footprint of mining.

Europe barely present – but even that is too much

Europe is rather a blank spot on the mining map. Although an overview by Cambridge University shows significant shares of the global hashrate from Germany and Ireland, the researchers put this into perspective: They know of no evidence of large mining farms in the two countries, which is why the values presumably come from IP diversions.

The only relevant mining location in Europe seems to be Sweden, where a good 1 per cent of the global hashrate comes from. The north of the country in particular is a sought-after location because of the cheap hydro energy and cool temperatures, which also benefits from the exodus of miners from China. At the very least, electricity consumption in northern Sweden has increased by several hundred per cent as a result of the ban in China.

One could welcome this. But even this globally microscopic European contribution already seems too much. Representatives of the Financial Supervisory Authority and Environmental Protection Agency in Sweden, for example, complain about the high energy consumption of mining. The government representatives state with concern that miners consume as much electricity as 200,000 Swedish households. “This is a development that we must stop.”

They therefore suggest that the EU “look into banning the energy-intensive mining method ‘proof of work’.” Other consensus methods, on the other hand, should be allowed and even encouraged. While the EU is looking into it, they say Sweden should already go it alone against crypto miners; companies that “want to be compliant with the Paris Agreement should no longer be allowed to call themselves sustainable if they trade or hold cryptocurrencies generated by Proof of Work. “

The two are, of course, aware that such measures can have their downsides. “The risk is that this will cause crypto producers to move their operations to other countries where they will potentially create greater emissions.” But Sweden and the EU should “take the lead and pave the way to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.” In an extreme misreading of the game-theoretical incentives of markets, the pair hope that other countries will follow the EU’s lead, i.e. that there will be a total global ban on bitcoin mining.

To make this point clear: Any scenario other than a global bitcoin ban – that would be a mining ban, after all – would increase CO2 emissions as Sweden drives its renewable hydro miners out of the country.

Instead of the world following the EU, the EU would follow China’s example: It doesn’t matter whether a measure harms the climate or not – the main thing is that we have a clean slate. The Paris Agreement becomes a pretext for shirking responsibility and a justification for acts that increase global CO2 emissions instead of reducing them. Policymakers are taking a symbolically effective measure even when in fact and as we know it has the opposite effect.