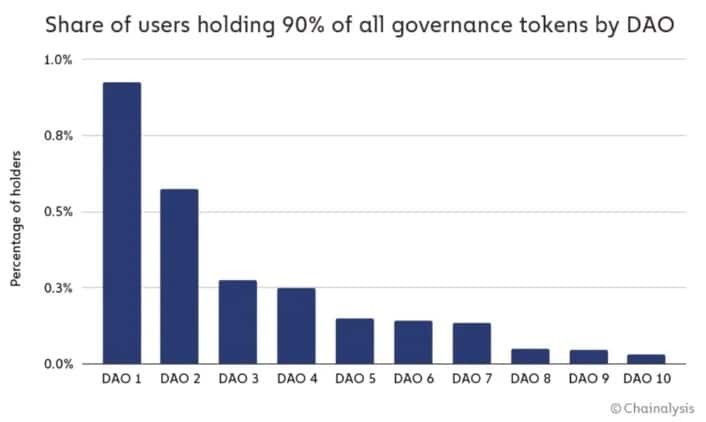

In a study on DAOs, Chainalysis shows that out of the top 10, voting power is concentrated on less than 1% of the actors. This observation leads us to question the real decentralisation of these

Chainalysis publishes a survey on DAOs

Chainalysis, the blockchain analysis specialist, has unveiled a survey on decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs). Part of this study focuses on their lack of decentralisation.

Indeed, these organisations are built in such a way that the voting power is distributed in proportion to the number of governance tokens owned. If there is a high concentration of these tokens among a small population of actors, this can lead to further centralisation.

Of the ten main DAOs in the ecosystem, Chainalysis notes that they all concentrate voting power on less than 1% of the governance token processors.

Figure 1: Share of users with 90% of governance tokens

As shown in the graph above, this centralisation goes as far as to see 7 of these 10 DAOs where 90% of their governance tokens are distributed among less than 0.3% of investors. This means that only a few people can influence the direction of the project.

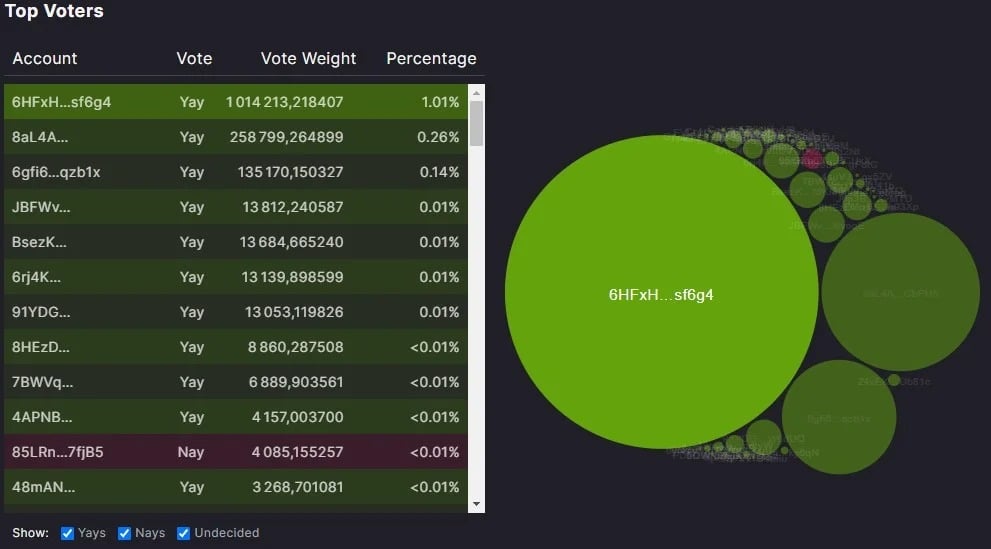

This limitation was also seen in a recent series of votes involving the Solend protocol (SLND). When the protocol was in danger of a large position, close to liquidation, three votes were held to try to find a solution. Of these three votes, one address alone could decide the outcome, yet the project developers did not take part in the ballots:

Figure 2: Distribution of voting power on a Solend governance proposal

In the example of the governance vote above, which totalled 1,504,822 votes, the address “6HF […] f6g4” alone accounts for more than 1 million of these votes. Although the ‘yes’ side would still have won without this actor, this actor alone could have won the ‘no’ side.

Moreover, it appears that the community does not always exercise its right to vote, leaving the field open to more involved actors. This abstention was particularly evident in this vote:

Figure 3: Result of a governance vote including abstention

The analysis of the results shows that less than 2% of SLND owners voted. Combined with the fact that only one address tipped the balance, this cannot be representative of the overall trend.

The distribution of governance tokens

This finding actually shows the limits of decentralisation in decentralised finance (DeFi). Indeed, if the fundamental principle of DAOs allows for real democracy, the reality is different.

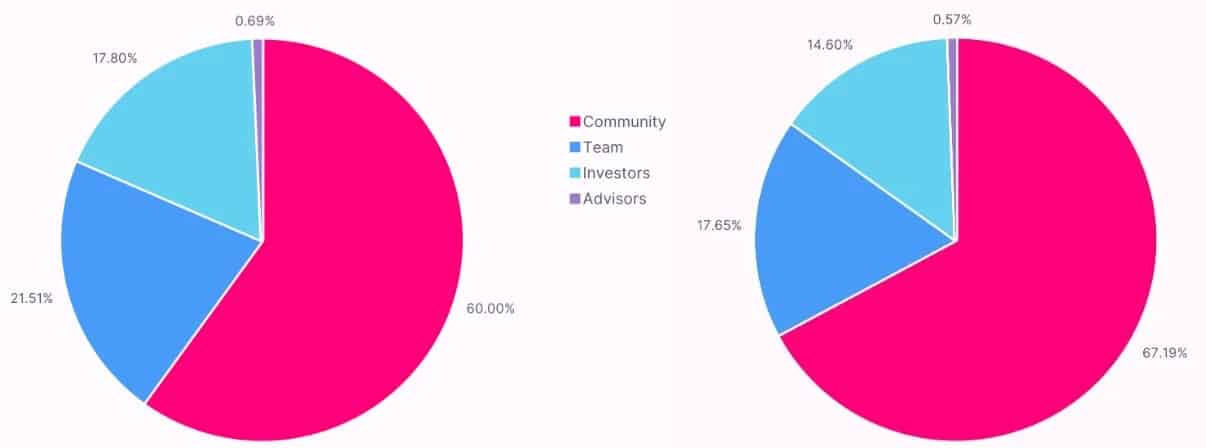

For a protocol to be truly decentralised, there should be a fair distribution of governance tokens. However, these are first allocated to the founding team and the first investors, while the community shares the remaining tokens. To illustrate this distribution, we can for example look at Uniswap (UNI) tokenomics:

Figure 4: Uniswap protocol tokenomics

Although these tokenomics have a relatively even distribution, it is useful to see the different power relationships. On the left, we have the initial distribution of UNI tokens, while the graph on the right is projected with 10-year inflation.

Thus, the community shares 60 to 67% of the UNIs in circulation, while this value varies between 21.51 and 17.65% for the team. The rest goes to the early investors and advisors.

For each DAO, tokenomics should be studied to understand the distribution of voting power.

The limits of this distribution

However fair tokenomics may be, it is important to understand that nothing prevents the founding team of a protocol from buying additional tokens from the community. This then increases their voting rights. If, in addition to this, we take into account abstentions, we realise that the decision-making power remains centralised.

However, this is not necessarily bad in itself. It is useful for a protocol to have some centralisation, at least in its early stages, in order to maintain a navigational course.

In addition, it allows the team to have flexibility. Let’s say a critical flaw is found, but its resolution requires a governance vote. By the time the governance vote is complete, a hacker could be doing damage.

However, as our ecosystem becomes more and more open to institutions, they have the financial means to acquire large quantities of tokens. This may lead to votes in their own interests, which may not be aligned with those of users.

As Chainalysis points out, DAOs will have to find the right balance between centralisation and decentralisation. These entities are still young and need to experiment to find the most effective model. As the ecosystem develops, these organisations will undoubtedly evolve.